(1866-1950)

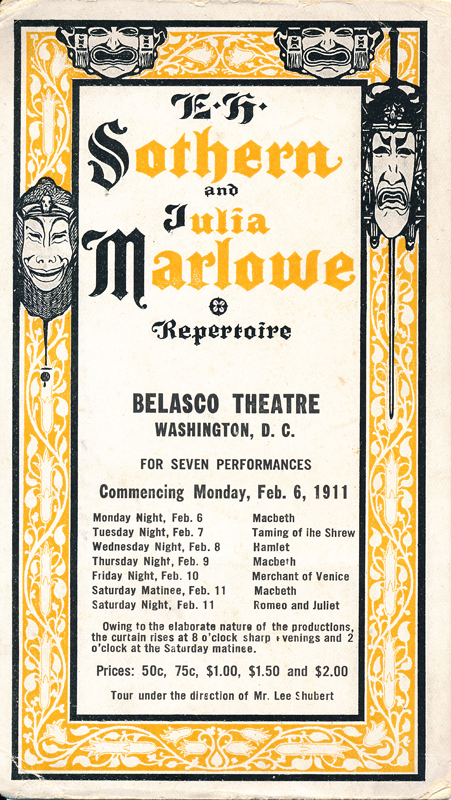

Sarah Frances Frost (Marlowe’s birth name) was born in England and came to the United States as a child in 1870. Her first stage appearance was in 1878 in Gilbert and Sullivan’s H. M. S. Pinafore. She was always popular with her audiences, and over the years became famous for her roles as Juliet, Viola, Rosalind, Beatrice, and Portia. After a stressful and failed marriage to and divorce from the ambitious actor Robert Taber, in 1904 Marlowe began performing with her second husband-to-be, E. H. Sothern, himself a distinguished Shakespearean. Although Marlowe was already a Broadway star in her own right, and was considered to be the best actress in the country, their first success as a team was in Romeo & Juliet in 1904. Seven years later, they married.

In 1907 she returned with her husband to England and as a member of Sothern’s company excelled in various plays in the company’s Shakespeare repertory. However, much of their major success was on Broadway. For a short time, they introduced Shakespeare to a much wider audience by performing many of his works at affordable prices at the Academy of Music in New York. She and her husband made eleven phonograph recordings of Shakespeare scenes between 1920 and 1921. She performed chiefly in the plays of Shakespeare and worked almost constant until her retirement in 1924. Later in life, George Washington University and Columbia University each conferred upon her honorary doctorate degrees. During her own lifetime, she was the subject of two biographies, one by a John D. Barry (1899) and another by Charles Edward Russell (1926), one of the founders of the NAACP.

Marlowe became somewhat of a recluse after Sothern died in 1933. They had no children, and she passed away in 1950 at the age of eighty-five.

From around 1895 owned and lived at the mansion at 337 Riverside Drive, New York City. Marlowe financed the townhome with the profits from her many Broadway successes, including both Shakespeare roles and her acclaimed role as Mary Tudor in Paul Kester’s adaptation of When Knighthood Was In Flower.

Marlowe’s stage prowess was well-acknowledged and long-lived. One reporter, in a 1903 edition of The New York Sun, noted of Marlowe: “There is not a woman player in America or in England that is—attractively considered—fit to unlace her shoe.”