Shakespeare’s Players on Postcards

By Harry Rusche, PhD

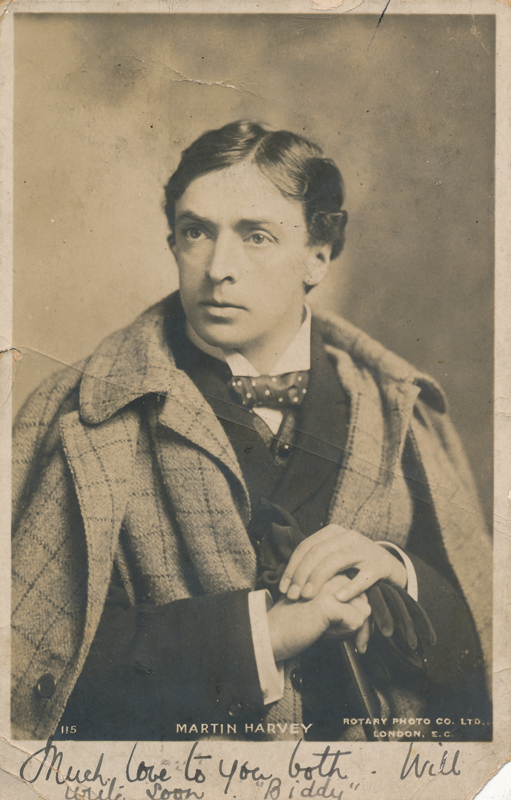

How many of us would think of postcards when we study the history of the theater at the turn of the twentieth century? I have for years been a collector of postcards related to Shakespeare, so for me these photographs of actresses and actors come immediately to mind.

Lest these ephemeral bits of paper seem too marginal and trivial, let’s put the topic of Shakespeare and postcards in perspective. For deltiologists (a name with which we attempt to dignify our hobby) the “golden age” of postcards corresponds roughly with the first decade of the twentieth century when picture-postcard collecting became a worldwide phenomenon—a mania, in fact. Richard Carline, writing in 1971, says:

Those who only know the postcards of today can scarcely be expected to appreciate what they meant to people sixty or more years ago. Many of us seldom think of buying a picture postcard, except as a matter of convenience; but during the quarter of a century that preceded the Great War in 1914, it would have been hard to find anyone who did not buy postcards from genuine pleasure. (9)

Everyone, it seems, bought, mailed, and collected postcards; even Queen Victoria had her own collection of cards. I am not sure what Queen Victoria collected, but a significant part of some collections featured the popular performers of the day, handsome and beautiful matinee idols.

In 1911, one facility, the Atlantic City Post Office, sold in that single year 17,000,000 one-cent stamps, most of them destined to be stuck on postcards. At Christmas, 1909, more than one million postcards were handled by the Baltimore Post Office, and the St. Louis Post Office cancelled 750,000 cards on a single day in that same Christmas season. The postcard mania was indeed in full swing in the first decade of this century. Dorothy Ryan suggests that the:

sheer number of postcards sent through the mails at the height of their popularity is staggering. In 1906 the Post Card Dealer reported that Germany’s annual consumption was 1,161,000,000; the United States’, 770,500,000; and Great Britain’s, 734,500,000. Official United States Post Office figures for the year ending June 30, 1908, cite 667,777,798 postcards mailed in this country. By 1913 the total in this country had increased to over 868,000,000, and by this date the craze was reportedly on the decline! (22)

“A rough guess,” Richard Carline proposes, is that in 1905 about seven billion postcards were handled by the various postal services worldwide; his source is Picture Postcard Magazine, September, 1905 (64). If we conservatively estimate, just for the sake of argument, that .0001%, a modest number, of the 734,500,000 cards sold in Great Britain in 1906 incorporated some aspect of Shakespeare’s life or plays, then we have 73,450 postcards dealing with the playwright, a lot of Shakespeare for just one country.

Hundreds of companies were created to meet this staggering demand for picture postcards; many were local concerns that published just enough cards for their own little souvenir shops or postcard racks. Many of them were, on the other hand, large concerns that turned huge profits. Several companies in the United States were noted for the quality of their work, but Great Britain and Germany produced cards that could truly be described as works of art. All these companies published their share of cards devoted to Shakespeare and his works. The most productive and imaginative company by far was that of the British firm, Raphael Tuck.

The innovative marketing ideas of Tuck gave the company its edge; they were the first to reproduce and even commission famous artists to paint scenes and images for their cards. In 1900, they published several series of cards with the works of J. M. W. Turner, Edward Landseer, and Marcus Stone; that same year they published a series of the paintings of the Dutch Masters in the National Gallery. In 1903, Tuck inaugurated its “Connoisseur” series of famous paintings, and the reproduction and fidelity to the originals were exquisite. But Tuck was not always so high-minded; the company also devised some brilliant sales gimmicks to keep the hobby of postcard collecting thriving. For several years Tuck offered cash prizes to those who had the largest number of Tuck cards in their collections; a collector had to have at least thousands of cards even to think of entering the contests. In fact, the prize of £1,000 offered in 1900 went to a lady in Norwich who had in her collection twenty thousand Tuck postcards (Carver 7). Other companies, to keep up with the competition, followed Tuck’s lead and began to think primarily about collectors as they designed their lines of cards.

Given the mania for postcards among the collectors at the beginning of the twentieth century, little time passed before the postcard publishers saw a potentially huge market in studio portraits and actual scenes from plays. The photographs of matinee idols—stars like Henry Ainley, Lewis Waller, and Matheson Lang—seem to have been particularly desired by collectors (many of them young women); for the men there were cards of actresses, some of them bordering in their poses and costumes on the sexually suggestive. Some of the most popular were the stars of the music hall. These women spent so much time in the photographic studios that they must have had precious little time to do much performing.

The number of cards dealing with Shakespeare, besides telling us something about the popularity of his plays at the turn of the century, are important as a resource for the history of the theater. The Victorian and Edwardian theater-goers loved pantomime, the music hall, and plays staged with spectacular scenery and effects. They expected and got “authenticity” and grandeur in the costuming and staging of their Shakespeare plays; Julius Caesar should, for example, look like Caesar’s Rome on the stage and the actors should be dressed like Romans from the first century BCE. The actor-managers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, you may be sure, outdid one another and gave their audiences what they wanted.

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree used live animals and plants in his 1900 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Richard Flanagan, the Manchester theater-owner (Queen’s Theatre) and impresario, may have used a live bear in a production of The Winter’s Tale. If a play called for a stream or a waterfall, then that is just what he built for the production of the play; to increase the effect and heighten the drama, he usually had an orchestra playing throughout his Shakespeare productions. It is said that when the audience applauded for a particularly striking effect on stage, Flanagan would come out, bowler in hand, go to center stage, and take a bow! In his production of Julius Caesar, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree hired dozens of extras to swell the mob of plebeians when he delivered Marc Antony’s eulogy. To create “pictorial realism” he used live animals and plants in some of his productions, horses in Richard II, and a donkey (as well as streams and waterfalls) in The Winter’s Tale. James Woodfield quotes Gordon Crosse who commented on one of Tree’s productions where it took an “unconscionable time” to tear down and change scenery. The audience sat and looked at the drawn, blank curtain for a total of forty-five minutes. When special effects and spectacle dominated the production, something had to give way to make extra time, and it was usually passages of Shakespeare and in some productions whole scenes. Crosse says that a full one-third of the text for that particular play was omitted (Woodfield 137; Crosse 37).

One more observation about a production emphasizing “pictorial realism”: J. C. Trewin in Shakespeare on the English Stage describes an “indulgent picture-book” production of As You Like It mounted by Oscar Asche at His Majesty’s Theatre in 1907. Asche used “a collection of moss-grown logs, two thousand pots of fern, large clumps of bamboo, and leaves by the cartload from the previous autumn. In one of his big sets the cast walked through ferns, two feet high in places, that had to be renewed weekly.” The setting was topped off by “a straw-thatched cottage in a garden at the edge of a pine wood” (47). A study of the cards on this site reveals that these particular productions, albeit perhaps a bit more extravagant, were not exceptional in the theaters of the first decade of the twentieth century. In response to criticism of their overwrought stagings, the actor-managers who mounted these lavish productions defended their practice with Shakespeare’s own words; they turned to the chorus of Henry V as Shakespeare’s apology for his inability to do all that he wished because of the limitations of the theatrical space he had to work in. “O for a Muse of fire,” the Chorus laments in the Prologue,

. . .that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene! . . .

Can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? Or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt? . . .

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them

Printing their proud hoofs i’ th’ receiving earth;

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there; jumping o’er times,

Turning the accomplishment of many years

Into an hour-glass. . . (1-33)

In Shakespeare Refashioned: Elizabethan Plays on Edwardian Stages, Cary Mazer quotes both Beerbohm Tree and the actor Arthur Bourchier as defenders of the then current theatrical realizations:

Tree saw the speech as proof that “Shakespeare . . . not only foresaw, but desired, the system of production that is now most in public favour,” i.e., verisimilar scenic embellishment. “Shakespeare,” according to Tree “not only counted upon the potentialities of his own theater to give point and life to his text, but . . . he also, with the prophetic eye of his genius, foresaw the time when a later stage would achieve for him, in the way of scenery, costumes, and effects, what the playhouse of his day was powerless to accomplish.” In other words, Shakespeare, had he lived in 1900, would have been an aide-de-campe of Tree at Her Majesty’s Theatre. [Echoing Tree’s interpretation of the Chorus in Henry V, Bourchier asserted] that Shakespeare “wrote his plays in the hope that some day they would be acted and staged better than they could be acted and staged in his own time.” (50-1)

None of my cards shows a live bear, but they do show us the costumes and scenery popular from about 1890 to 1914, the dates of most of the postcards. Some of the postcards are especially valuable because they show us scenes perhaps no longer available from any other source; some of these photographs may look familiar and they are reproduced in some books on the Victorian and Edwardian stage. The pictures had multiple uses and they appeared on posters, handbills, in theater programs, as photographs to be autographed for fans, as “cabinet photographs,” and even the carte-de-visite, the cards left when people called upon one another socially and for business. The same photograph served many purposes, and sometimes the postcards were used as advertisements for companies on tour and sent to patrons before they reached the various cities where they were scheduled to perform.

The cards are also valuable to historians of the drama because they document for us the end of an era in the British theater. The time of the actor-manager was slowly slipping into another phase, the day of the modern theater where the director and producer were to control the production of Shakespeare’s plays and the players who acted in them. A London theater season never went by without the companies of Sir Henry Irving, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, and Sir Frank Benson reviving in repertory as many as a dozen Shakespeare plays. The companies of the actor-managers were fairly stable, and they depended on actors and actresses who could change from role to role and play continuously throughout the season. Auditions for individual plays were unnecessary; actors were hired and became part of the company until, like Dame Ellen Terry and Matheson Lang, they sometimes struck out on their own and temporarily formed their own companies. Dame Terry, who played with Sir Irving most of her adult career, several times presented her own productions of Shakespeare, but she always returned to the Irving fold.

The beginning of the end of the actor-manager system was at the time so subtle that it was perhaps not even at first noticeable. William Poel, himself an actor and theater manager, founded the Elizabethan Stage Society in 1895; the Society’s stated purpose was to revive the old plays, and especially Shakespeare, and perform them as closely as possible in the same way that the Elizabethans would have done. The DeWitt sketch of the Swan Theatre had been uncovered in 1888, so the Society had just that much more evidence to tell them what a performance might have looked like in 1600. Poel’s productions therefore used a thrust-stage, minimal scenery and music, Elizabethan costumes that hardly indicated the period that the action of the play represented, and no curtain or proscenium. Two of his notable attempts were Measure for Measure in 1908 and Troilus and Cressida in 1912. Poel’s intention was to strip Shakespeare of all the Victorian/actor-manager excesses of scenery, spectacle, and “pictorial” or “historical realism”; the text and the poetry, he insisted, would sustain the performance of a Shakespeare play.

Poel’s productions of more than a dozen plays attracted admirers (and detractors as well), but he was not alone in experimenting in the theater and we begin to see in the first part of the century the names of other innovative directors like Granville Barker, Edward Gordon Craig, and Huntley Carter, all calling for a “new stagecraft” to replace the antiquated Victorian notions of theatrical spectacle. April 29, 1905, may be as good a symbolic date as any to mark the approaching end of a tradition; Sir Henry Irving began on that day his final London season, and he played one of his most famous roles, Shylock. At any rate, by the end of the Great War, like so much of the rest of the world, the theater had changed; these postcards of various productions of Shakespeare are a reminder of a time that has slipped into theatrical history.

Granville Barker, in several controversial productions, indicated the way the “new theater” was to go. He produced The Winter’s Tale at the Savoy in 1912 with some radical changes in method. First, and perhaps most important, he restored the entire text of the play and directed his players to speak the lines with what was considered an unacceptable speed. The scenery was minimal and the costumes were stylized and tied to no particular historical period. The production ran for six weeks, and in November 1912, Barker presented Twelfth Night, again with a simple set and costumes that were distinctly non-Elizabethan. As with his earlier production, the language of the play was spoken in a rapid but rhythmic style. The critics seemed less averse to this production than they were to his first attempt with The Winter’s Tale. His most controversial production, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, appeared a few years later in 1914 at the Savoy; this was to be his last production at the Savoy and Barker contented himself with writing about Shakespeare is his exceptional introductions to various plays. The critics were either hot or cold on this unyieldingly “modern” version of the play: the fairies were more like elves, Puck was dressed in scarlet, curtains lighted in various colors served as the backdrop, English folk songs for music, and nothing looked the least bit traditional or, for that matter, real. After ninety-nine performances at the Savoy, Barker moved the production in 1915 to New York and Wallack’s Theatre. A Midsummer Night’s Dream was no less shocking there than in London, and the reviews were mixed. But no matter what the critics had to say, Granville Barker had made an indelible mark on the Shakespearean tradition, and critics like William Winter were fighting a battle already lost. The virulence of the attacks on Granville Barker are revealed in these remarks by Winter in Shakespeare on the Stage (third series, 1916):

THE GRANVILLE BARKER PRESENTMENT

On February 16, 1915, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” was presented at Wallack’s Theatre by the English actor and manager Granville Barker in what has been loftily vaunted as the “modern” manner. As a performance of Shakespeare’s lovely poetic play the presentment was a desecration, but it provided a representative example of the nauseous admixture of mental decadence and crotchety humbug absurdly designated “progressive” and foolishly accepted by irrational persons and by others who seek to run with every vagary of the hour,—fearing to protest against pretentious quackery lest they should be reprehended as “reactionary,” “hidebound,” and “not up to date.”. . .

Illusion was never created. The absurd scenery was destructive of all right effect. It is impossible for the mind to abandon itself to the enchantment of the acted drama and allow itself to drift with the representation, self-forgetful and delighted, when it is continually compelled to consider that trees are indicated by long festoons of gray cloth, wooded banks by wooden benches, and flitting sylphs by prancing gnomes that no more suggest fairies than so many coal-scuttles would! (281-96)

Winter needs fifteen total pages to excoriate Barker and this “obscene” production, so unlike anything he admired about the plays presented by the great actor-managers, Tree, Irving, Greet, Benson, and all those actors touring the entire world.

Postcards on Shakespeare appeared in a dizzying array of contexts, some humorous and some serious; these cards of actors were only a small part of Shakespeare and of the card-industry as a whole. Many cultural influences made Shakespeare postcards popular, but the simplest explanation for the one thousand cards mounted on this site is that the public was caught up in a mania for collecting that is easy to understand. These were pictures of the most popular stars of the day, and handsome men and beautiful women are always popular in any medium. Actors, like our movie stars today, had an irresistible appeal, and there was no shortage of actors and actresses to collect; London was home to almost fifty theaters when playgoing was one of the city’s major entertainments.

A NOTE ON SOURCES

To learn more about the history and range of the postcard, I recommend these books to which I refer throughout the text: Anthony Byatt, Picture Postcards and Their Publishers (Malvern: Golden Age Postcard Books, 1978); Richard Carline, Pictures in the Post (London: Gordon Frazer, 1971); Sally Carver, The American Postcard Guide to Tuck (Brookline, MA: Carves Cards, 1982); A. W. Coysch, The Dictionary of Picture Postcards in Britain, 1894-1939 (Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1984); and Dorothy B. Ryan, Picture Postcards in the United States, 1893-1918 (New York: Clarkson Potter, 1982).

In The Shakespeare Trade: Performances and Appropriations (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1998), Barbara Hodgdon talks about “Shopping Shakespeare” (232-40) and the endless array of items for sale in the town’s shops and the museum gift shops. In such shops, there are, of course, dozens of postcards to choose from, but the tourist can also buy memorial medallions, spoons, china and glass, a “Shakespeare saving bank,” plaques, boxes, books on Shakespeare (and even his plays), coloring books, paper dolls, tea towels, potholders, Christmas ornaments, T-shirts, and thimbles. If you have ever visited Stratford-upon-Avon, you know the list is formidable, and all the items bear an image of something Shakepearean.

Cary M. Mazer has an excellent discussion of the changes that took place in Shakespeare performance during the early decades of the last century in Shakespeare Refashioned: Elizabethan Plays on Edwardian Stages (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1981). See especially the section entitled “Shakespeare and the New Stagecraft” (85-121). Another important source is James Woodfield’s English Theatre in Transition, 1881-1914 (London: Barnes and Noble, 1984). Of interest too are Gordon Crosse, Shakespearean Playgoing, 1890-1952 (London: A. R. Mowbray, 1953) and J. C. Trewin, Shakespeare on the English Stage, 1900-1965 (London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1964). See our bibliography for more sources.

Also, take a look at “Moments of Note: Players on Stage” for a chronology of performances interspersed with major world events.